TL;DR - By exploiting Webpack’s async loading feature you can roll a feature-gating mechanism in your JavaScript app that only loads the code your end user is supposed to see. This is great for beta testing features and making smaller initial loads. You probably don’t need to do this in your application.

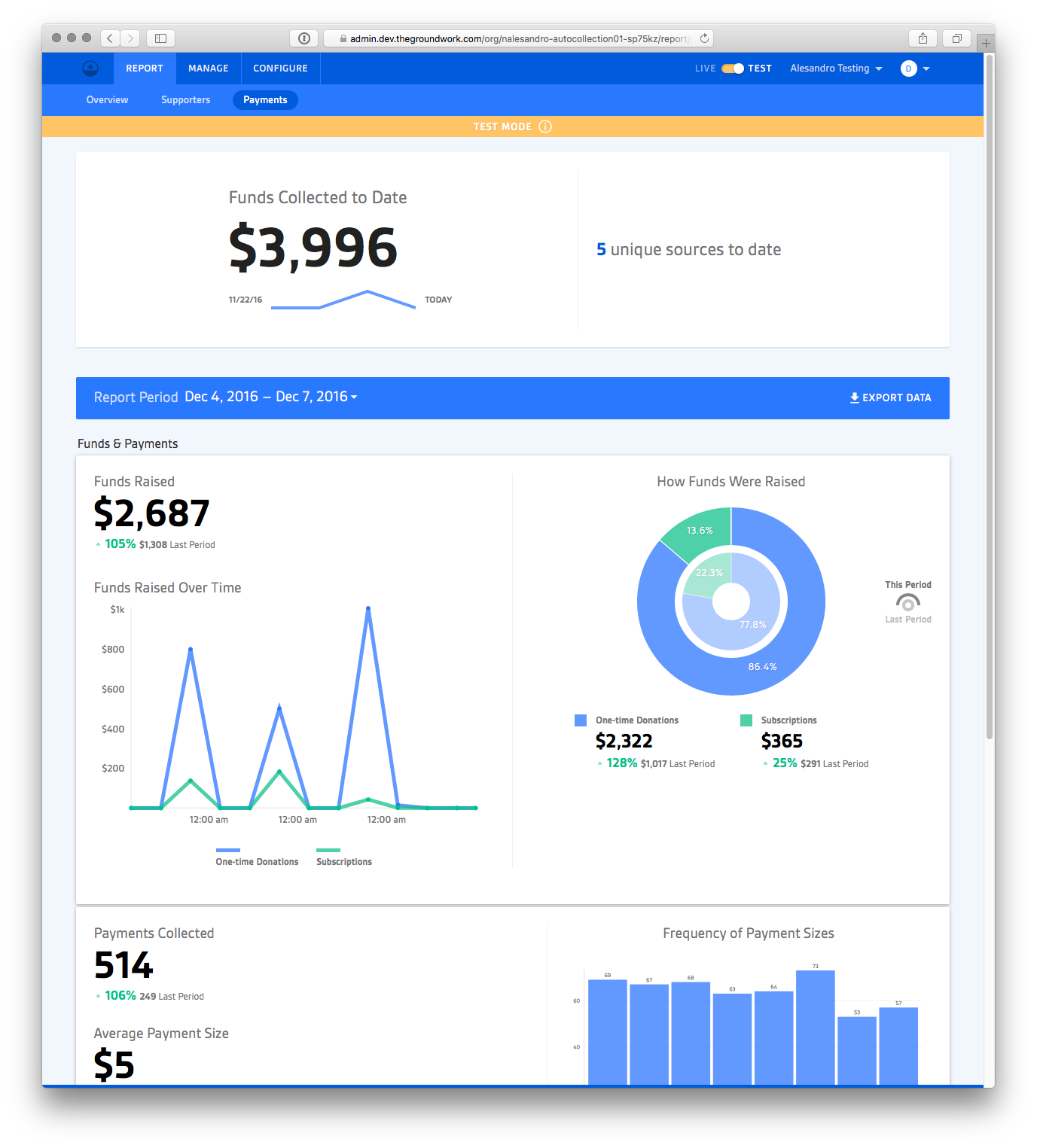

For the past year I’ve been working with an extraordinary team building an administrative interface for The Groundwork, a SaaS technology platform built to help nonprofits collect supporter data, raise funds, host events, measure progress, and more. This has been extremely fulfilling work, primarily because our platform is purpose built to help organizations like the UNHCR and similar non-profits/NGOs. Aside from the mission and clients, building Admin (yes, that’s what we call the administrative application - catchy isn’t it?) has been a treat as it’s presented us with a number of tasty challenges.

Oh, by the way: You can read an excellent design overview about Admin from my developer-in-arms Nikki Lee.

Image: Screenshot from Admin, specifically the Reporting view detailing funds raised by an organization.

When planning the initial architecture for Admin I was presented with a few challenges right off the bat:

- The application would be large, so I wanted a way to manage the file size of our JavaScript payloads.

- We wanted to use feature-gating, so that specific customers could be served different versions of the application, or not have access to specific parts of the application at all.

- At any given time a number of designer/developers would be working on the application concurrently, so I wanted a clean(ish) separation between pieces so we wouldn’t get into each others hair while working.

- The underlying platform APIs would be shifting (or non existent) while we worked on the application.

After some time noodling through the problems and hacking on some ideas, I settled on the front-end stack du jour: React / React Router / Redux / Webpack / Babel (or The RRRWB Stack as I never, ever, call it). These libraries provided a lot of tools and features which helped me deal with the project requirements and provided numerous conveniences, such as the abilities outlined below.

Code splitting / async loading

Webpack provided an easy win for the first requirement with its ability to break and application into multiple JavaScript files. The CommonChunkPlugin let us divide our application and library code into separate compiled files (app.js and vendor.js respectively). vendor.js is a fairly hefty file, but it contains all of the library code we need for the app and is only loaded once at the beginning. app.js is a smallish file which contains the bare minimum of application code needed for the initial page load, again only loaded once.

The other big win was Webpack’s concept of split points which allowed us to subdivide the application code further. Using require.ensure to pull in modules (instead of ES6’s import or the regular variant of CommonJS require) tells Webpack to split the app code into individual numbered files, (ex: 13.js) that are requested via Ajax and loaded into memory. What this essentially gave us was a “load on demand” architecture for the rest of the application past the initial load of app.js and vendor.js. We were able to achieve this through a nice trick tucked away in React-Router: dynamic asynchronous routes. You can see an example of this within their huge-apps demo. This is an example of one of our routes:

export default {

path: 'events',

documentTitle: 'Manage Events',

getChildRoutes(location, cb) {

require.ensure([], (require) => {

cb(null, [

require('./routes/CreateEvent'),

require('./routes/Event')

]);

});

},

getComponents(location, cb) {

require.ensure([], (require) => {

cb(null, require('./components/ManageEvents'));

});

}

};

When you navigate to /events in Admin, an XMLHttpRequest is made for the correct component file and loaded into memory. The system is smart enough to only load them once. Webpack provides this essentially for free (after sweating through the elaborate configuration details).

This does add some complexity to your application, in that you cannot define your Routes all up front in JSX as one normally does with React-Router (example). We adopted a file structure similar to the huge-apps example that bundled the route definitions within the index.js file into folders with their components and child routes:

src

├── routes

│ ├── ManageEvents

│ │ └── 0.0.1

│ │ ├── __test__

│ │ ├── actions

│ │ ├── components

│ │ ├── config.js

│ │ ├── index.js

│ │ ├── reducers

│ │ ├── routes

│ │ ├── selectors

│ │ └── utils

This helped solve two of my bullet points: Load the app on demand to keep initial file size down and also break the app into discrete routes, or higher-level components, which developers could work on independently without stepping on each others toes too much. The next big problem to tackle was feature-gating the application.

Feature gating

Feature gating boils down to: use some criteria to present different code paths to different users. In its simplistic form this could be something like:

import Bar from 'bar';

import Default from 'default';

import Foo from 'foo';

import User from 'user';

switch (user.getFeature('events')) {

case 'FOO':

render(Foo);

break;

case 'BAR':

render(Bar);

break;

default:

render(Default);

break;

}

There are lots of ways to approach this, and you can use feature gating for many different things: beta testing new code, restricting access, deploying custom features for specific users, etc. There are few things to consider when setting up a system like this:

- How do you define which code path a customer follows?

- How do you get that information to the application?

- How do you branch the code based on that criteria?

In our case we not only wanted to change code paths on a user by user basis, we wanted to do it a level up, on an organization by organization (org) basis (an individual user in our system always belongs to an organization, such as UNHCR). We also wanted to completely switch off parts of the application at an org level.

Luckily, as we had already implemented async code loading based on routes, we already had an entry point. By controlling the routes given to React Router we could control what code was loaded into the application, sparing a user the kilobytes for modules they didn’t need nor had access too. To pull this off we leveraged some interesting features of our platform.

The Groundwork is built on a micro-service architecture. A big part of running micro-services is configuration management, ensuring all the individual services know where to find each other and configure themselves properly on startup. Early on we leveraged Consul to help with configuration and service discovery, using it as is and building additional services on top of it. One of those additional services was a system which allowed us to store information about each organization that uses our system. We could use this system to store feature metadata for each org, requesting it on demand to build the routing tables for React Router when the application bootstrapped on page load.

To pull this off we created two different sets of metadata: Feature Definitions, which were stored in Consul and specified what components an org has access to, and a Component Catalog compiled into the application which provided a directory of all the available components within the app (but not the component code itself.)

Example feature definitions (JSON - stored in Consul on a per organization basis):

[

{

"AccountWorkspace": {

"version": "1.0.0",

"children": [

{

"accountChangePassword": {

"version": "1.0.0"

}

}

]

}

},

{

"OrgSettingsWorkspace": {

"version": "1.0.0",

"children": [

{

"orgSettings": {

"version": "1.0.0"

}

},

{

"orgSettingsAdmins": {

"version": "1.0.0"

}

},

{

"orgSettingsBilling": {

"version": "1.0.0"

}

}

]

}

}

]

Example component catalog (JavaScript - compiled into app.js):

const catalog = [

{

feature: 'AccountWorkspace',

version: '1.0.0',

path: '/account',

route: {

path: '/org/:org/account',

component: require('./containers/AccountWorkspace')

}

},

{

feature: 'OrgSettingsWorkspace',

version: '1.0.0',

path: '/organization-settings',

route: {

path: '/org/:org/organization-settings',

indexRoute: require('./routes/OrgSettings/1.0.0'),

component: require('./containers/OrgSettingsWorkspace')

}

}

// ...

]

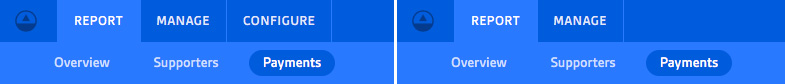

When the application bootstrapped on initial page load it would take the Feature Definitions provided by Consul and combine them with the Component Catalog to produce two new objects: our Global Navigation tree and a React Router routing table. This means that the Feature Definitions from Consul determine how we render the navigation of the entire application (including in what order items appear in the nav system) as well as the available routes. If you don’t have access to a component, a link to it is never rendered in the application.

Image: In the navigation example on the right, ConfigureWorkspace was removed from the feature definitions, removing Configure from the tabs and the application as a whole for that organization.

In addition to controlling access and order, we implemented a versioning scheme which would allow us to specify which flavor of a component to serve to particular orgs:

└── ConfigureIntegrations

├── 1.0.0

├── 1.1.0

├── 1.2.0

├── 1.3.0

└── 1.4.0

Our feature definitions for an org could specify which version of a component to load from the catalog. For instance, as the Platform team rolled out new features or API changes, we would create new versions of a component taking them into account. We could then deploy these changes to our dev environment and update our feature definitions in Consul to see the new verions. Additionally this provided a fail-safe in prod, as we could deploy the new versions and then only give ourselves access in the feature definitions for a final sanity check against prod data. We could then switch on the feature definitions for all orgs (or a subset) once we were happy.

This system definitely added some complexity to the application, but also provided a lot of power and flexibilty in how we developed and deployed code for the end users.

Top image: Pies, 1961 by Wayne Thiebaud

Comments